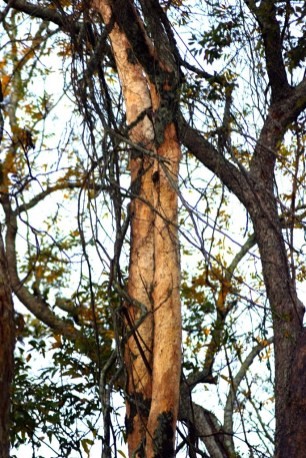

Like other woodpeckers, Ivorybills leave a mark on the trees they use for foraging. There’s something distinctive, and potentially diagnostic, about the Ivorybill’s signature of “bark scaling.”

Written by Mark A. Michaels, Research Associate

When I first started searching for Ivorybills, it struck me that James Tanner, who published the only comprehensive study of the species, and others frequently relied on the presence of feeding sign as a primary indicator of Ivorybill presence. It also struck me that this was a subject that had not been very carefully examined.

I soon learned that Campephilus woodpeckers, like the Ivorybill, have some unique anatomical characteristics – not just the large, chisel-like bill but also their musculature and foot and tail structures. This makes them uniquely suited to stripping tight, strong bark from dead and dying trees. Pileated Woodpeckers are capable of scaling bark too, as are squirrels. But years ago, I hypothesized that a narrow category of bark scaling might be diagnostic for Ivorybill. While the category has grown narrower with time, I remain convinced that some scaling is beyond the physical capacity of any other animal.

It has proven difficult to convey the nuances of what Project Principalis’s researchers look for in situ. I’m going to try a somewhat different approach using images that have been posted previously. I will be focusing on the category of bark scaling that I think is most compelling for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers and have added images of three additional types of work.

The only work we consider is on live or recently dead hardwoods – meaning twigs and small branches are attached, and the wood is hard or apparently hard. This is the decay class that Tanner described as “the kind that Ivorybills habitually feed upon” but that Pileateds use rarely, if at all.

The scaling I find most compelling for Ivorybills is on hickories, mostly or all bitternut hickories (Carya cordiformis). This work represents a relatively small subset of the suspected Ivorybill feeding signs we’ve found, as would be expected given that under 10% of trees in the area comprising our search are hickories. It is not the type of foraging sign that Tanner emphasized, and I’m not suggesting that scaling on boles is the Ivorybill’s predominant foraging strategy. This work has a distinctive appearance, one that differs dramatically from presumed Pileated Woodpecker foraging sign, seen below, on the same species.

The above images show presumed Pileated Woodpecker work on a recently dead bitternut hickory found in February 2016. It seems reasonable to infer that this is Pileated work because of its extensiveness and the abundance of fresh chips at the base of the snag, suggesting the work was recent and was done by a large woodpecker. Some readers might be inclined to think of this as “scaling”, when in fact it is shallow excavation. The small size of the chips and the fact that some of the chips are sapwood, not bark, support this idea. Contrast the roughened appearance of the sapwood with the clean bark removal in the images below. Also contrast the extensiveness; while the work shown above involves fairly large areas, it pales in comparison to the very extensive scaling we associate with Ivorybills.

As I see it, squirrels can also be ruled out for this work due to the involvement of the sapwood, apparent bill marks, and the presence of insect tunnels.

I believe that all of the images immediately below show Ivory-billed Woodpecker work, all of it on hickories and most of it fresh. The similarity in the scaling’s general appearance from tree to tree should be self-evident. This type of scaling can be found from within approximately one foot off the ground to the upper parts of boles. Large Cerambycid exit tunnels are visible in the sapwood. Bark chips, when found, were large, and the only hints of excavation involved targeted digging to expand the exit tunnels. It’s worth noting that the Hairy Woodpecker in the trail cam photo below spent several minutes removing a quarter-sized piece of bark. The Pileated Woodpecker also spent several minutes on the tree; it pecked and gleaned and looked around but did no excavating or scaling. More discussion below the images.

Bitternut hickory wood is “hard and durable” and the bark is hard and “much tighter than on most other hickories.” The bark is sometimes described as being thin, but this appears to apply to young trees only. On mature boles, it can be .5″ thick or more.

Due to these qualities, the decay process for hickory snags is often more gradual than for other species, especially in higher and dryer areas. This means that the wood can stay hard and the bark can remain tight for as long as three years; such is the case with the tree shown in the penultimate image above. This has enabled Project Principalis researchers to do periodic checks on some of the snags, and in most instances, they have shown little or no indication of further woodpecker work for extended periods, until the wood starts to soften and excavation becomes easier. Whatever is doing this work seems to be hitting the trees once or twice without returning or, less frequently, to be making visits several months apart. This suggests a thinly distributed, wide-ranging species as the culprit, and in my experience, Pileated Woodpeckers tend to return to feeding trees on a regular basis.

In my view, this very specific type of work is diagnostic for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker and is beyond the physical capacity of the Pileated Woodpecker.

I’d suggest that similar appearing work on boles and large, lower branches of other tree species should be considered strongly suggestive. Here are several examples – on sweet gum, oak, and honey locust – from both search areas.

When it comes to the high branch work that Tanner emphasized (as well as work high on smaller DBH trees), it is more difficult to rule out Pileated Woodpecker and squirrel, although if bark chips can be found they may provide some clues.

This is the type of foraging that Tanner found to be the predominant one during breeding season and immediately after fledging young, at least for the John’s Bayou family group in his study. Thus, for work higher on trees, where bark is thinner and tightness cannot be assessed, abundance is likely a key indicator. From this perspective, it may be significant that Ivory-billed Woodpecker searchers looking in the Pascagoula, Mississippi area have found only two sweet gums with work consistent with what’s described in the literature, this between spring 2014 and November 2016. By contrast, Project Principalis searchers found over 50 such trees in our search area in the 2015-2016 season alone.

Press inquiries: please contact [email protected] or call 412-258-1144.

Support this important project by directing your donation to Project Principalis

Support Our Work