First-hand reports of sightings of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are invariably controversial. Critics point to the fleeting glimpse often inherent in an observation, many times the lack of a corroborating observer, and the possibility of confusion with the similar Pileated Woodpecker. Skeptics also insist that eyewitness accounts are inherently unreliable because we can subconsciously trick the brain into seeing what we really want to see.

We agree that personal observations of purported Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are not enough to declare the species alive and well. However, here we offer first-hand reports by Project Principalis team members of apparent Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in our search area. We are struck by the quality of many observations, and by the fact that with the exception of two reports, all were seen within 1 mile of each other. We note the nearly universal and instant reaction to each sighting, dominated almost by a sort of suspension of belief, manifested in the tendency to simply watch the bird, fixated, with no effort to reach for binoculars or camera. Perhaps related to that reaction is that nearly every observer reported the impression of a unique, brilliant white, unlike anything seen in any other black-and-white bird. We hope you enjoy these accounts!

Note: In these accounts, Ivory-billed Woodpecker is sometimes shortened to “IBWO.”

From Frank Wiley, co-founder of Project Coyote (now deceased; as re-told by Mark Michaels):

On April 3, 2015, Frank and I hiked into the area we called the ‘hot zone.’ We did some playbacks of Ivorybill kent calls at approximately 8 am, although I did not record anything about them in my notes. We then proceeded walking in a more or less southerly direction with Frank in the lead by about 10 yards; I was walking slowly and looking up and to my right. As we approached a body of water, Frank stopped suddenly and blurted something unintelligible. I caught up with him, and he said he had gotten a very good look at a male Ivory-billed Woodpecker that had flushed, presumably from a fallen log lying in the water or possibly from along the water’s edge. The distance to the log was no more than 20 yards.

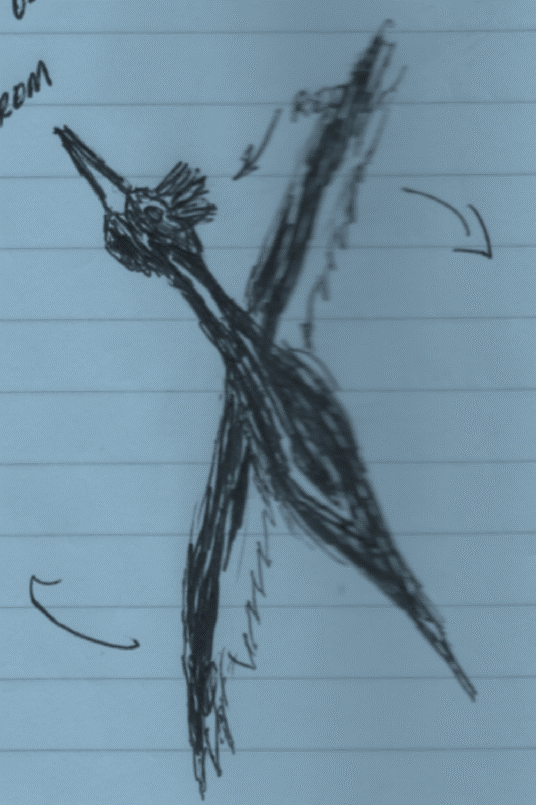

I handed Frank my field book so that he could draw what he saw and record his observations.

In addition to the sketch, I present a transcription of Frank’s description; I made a few redactions related only to the specific location of the sighting. These notes were made immediately after the sighting and without reference to a field guide.

Frank immediately noted:

- A big, traffic cone shaped WHITE bill (3”ish?)

- Solid black head/face – light colored eye (whitish)

- Bright red, crimson crest – puffed up (not what you’d expect)

- Stripe on face beginning below/behind the eye

- Stripes on back form chevron over rump

- Wings long/thin; shallow, rapid flaps

- Rear 1/3 to 1/2 of wings white, all the way out to primaries

- Long, tapered tail

Not included in the description was his estimate that the sighting lasted 2-3 seconds; the bird, was flying in the open for perhaps 10 yards as it flew upward, crossing the water, and then into an opening in the woods.

Later that same day in an email exchange, Frank added the following comments: “At the first sign of movement, I assumed a Wood Duck had flushed, looked in that direction, and immediately saw the crimson red of the crest. I then thought, “PIWO” [Pileated Woodpecker]but noticed the big white traffic cone bill, and an almost entirely black face. There was a white stripe that started below/behind the light (I got the impression of white – not yellow) colored eye. The crest was not “groomed” as is usually seen in most of the artwork – rather it was puffed up as if the bird were agitated.”

From Mark Michaels, 2016:

In fifteen years of searching, I have had perhaps a dozen possible sightings. All have been brief and all of them have led me to second-guess or minimize them in retrospect. People often point to confirmation bias in possible IBWO-sightings, and I work hard to challenge that tendency in myself. In some cases, I have retrospectively rejected sightings altogether. In others, I am left with varying degrees of uncertainty, and I sometimes feel that I’d be completely satisfied with just one good look!

With that said, I have one sighting from the current search area that is hard for me to explain away. I saw the bird first with the naked eye at a great distance. The lighting conditions were excellent. I got binoculars on the bird and I just can’t make it into a Red-headed Woodpecker or anything other than an Ivorybill.

This observation occurred at about 9:25 am on October 13, 2016. I was walking south and turned to my right, looking across a clearing to a large snag that I estimated to be approximately 200 yards away. (I later used a rangefinder to measure it at 160 yards). I texted my wife with a description of my sighting, and I then fleshed out the observation in an email that evening; that is included below. The bracketed remarks have been added for clarification.

“I saw a brilliant flash of white as a woodpecker flew up onto the tree [this was a dorsal view of the bird’s back]. I reached for my binoculars not my camera; I think because the distance was so great. I got the bins on the bird and got them focused as it took off. I didn’t get anything like a good look, but again saw brilliant white wings with a little black. I also had the distinct impression that the bird was much too large to be a RHWO [Red-headed Woodpecker]. But, it was a fleeting glimpse (or better, two fleeting glimpses). I did some playback of PIWO [Pileated Woodpecker] and IBWO and had no responses.”

“I . . . went to the snag. There is a RHWO roost at the very top, and I saw one juvenile and another RHWO, but didn’t see the head [and could not determine whether it was a juvenile or an adult]. Though RHWO’s were present, seeing them at this close range made me feel even more strongly that the bird I spotted was much bigger. I can’t fully rule out RHWO, but I also find it hard to imagine that I would have been able to get any details at all at such a distance unless the bird was large.”

This was my first possible sighting of an Ivorybill in almost three years. I was disoriented and shaken by it, as I have been with my handful of other possible observations. In addition, since it was not a good look, I can’t help but doubt myself.

As it turned out, Frank Wiley and I were able to spend some time observing Red-headed Woodpeckers in an open area at 50-100 yards. This was on the following Sunday morning at approximately the same time and under lighting conditions that were, if anything, somewhat brighter than those on Thursday. Those observations led me to lean somewhat more strongly toward Ivory-billed Woodpecker. While the white rump of the Red-headed Woodpecker was easily visible at these distances, the white on the wings at a similar angle of view appears a lot less extensive and vivid than what I saw, and Red-headeds indeed look quite small.

From Mark Michaels, 2021:

October 27, 2021: 7:54 AM stakeout at tree number one, Ivory-billed Woodpecker sighting, bird flying at canopy height east to west. (This was an excited error, compass showed direction was WSW to ENE.) Silhouette only, long neck and tail projections, rapid flight, and one clear wing tuck noted.*

Before recording the above I had yelled “Ivorybill!” Not ‘what was that’? Or ‘did you see that’? Or even ‘I think I saw one’. It was an expression of shock and certainty.

The sighting lasted perhaps 3 seconds. Skies were overcast, and no field marks were noted on a couple of Pileateds that flew by. The bird I saw did not remotely resemble a PIWO [Pileated Woodpecker] in profile, flight style, or speed.

My first impression when the bird entered my field of view was that it was a duck. Seeing the distinct wing tuck is what led to the shout.

In the aftermath of the sighting, I thought about what kind of duck it most closely resembled, and I came up with Common or Red-breasted Merganser as the best analogy. It’s possible I subliminally noted a crest, but I don’t have a conscious awareness of that. I looked at a field guide and thought, merganser’s a good analogy, but the tail’s too short.

I had always intellectually understood Tanner’s reference to Pintails. It’s apt in terms of neck and tail projections, less so in terms of body shape. This sighting deepened that understanding. Overnight, it struck me that the similarity in body structure to a diving duck might relate to some of the swooping and diving we see in one of the drone videos.

I’m really adept at questioning myself, but this was not a mistake about the position of the marks. The default to duck followed by the shock of seeing the tuck would seem to rule out some kind of expectation bias.

I have had nagging doubts about all my other possible sightings, even though I doubt the one from 2016 could be anything else. If I were serious about keeping a life list, this would be on it. That’s a first.

*For the casual reader, wing tucks are also known as flap bounding, a flight style that is universal or nearly so in woodpeckers, including the Ivorybill.

Tree #1 is the tree where many of the trail cam images shown in the preprint were obtained and where Don Scheifler, who was with me on this stakeout, had a sighting and took a cell phone photo in 2019. As is so often the case, he was looking in a different direction and did not see the bird, but he heard me yell and snapped the picture immediately afterwards.

Lest anyone think this was expectation bias, I had staked out Tree #1 many times during the 2019-2020 season without seeing anything. I have spent countless hours in the field over 15 years without seeing anything I could be absolutely sure was an Ivorybill. My expectation of having an encounter, visual or auditory, on any given day is extremely low. Any possible encounter is exciting, but this one was a shock albeit a delightful one.

I have an inner skeptic, something that has positive and negative aspects. On the plus side, I see it as a kind of healthy humility, a check against my own biases. On the minus side, it is, to some degree, a colonized response to the vitriolic debate around the Ivorybill and the cognitive bias imposed by conventional wisdom. A mindset that says, ‘The Ivorybill is gone, who you gonna believe, me our your lying eyes?’ It may come as a surprise, but this mindset is not uncommon among Ivorybill searchers.

I have had a handful of possible sightings in my 15 years of searching. My approach has always been to pick them apart in retrospect. The nagging doubts mentioned in my notes reflect that approach. In a few cases, they have led me to decide I was mistaken. In most, they have led me to place my observations in the ‘possible’ category. In 2009, I heard wingbeats and saw the underwings, but have had a little uncertainty due to the brevity of the visual observation, even though it was followed by what is, in my view, a compelling trail cam capture a week later. Similarly, in 2015, I couldn’t fully rule out Red-headed Woodpecker, though I see that possibility as being extremely unlikely.

I feel a kind of ethical obligation to rigorously interrogate my own perceptions, but even now, after almost 8 months, I can’t talk myself out of what I saw on October 27, perhaps because field marks are not an issue and there is no question about size. RHWOs [Red-headed Woodpeckers] and PIWOs don’t look like ducks. And ducks don’t tuck.

But there’s an even more elusive species of doubt involved, one that I hadn’t recognized before this sighting. Despite all my years of searching, despite my advocacy, despite being labeled a “true believer” in some quarters, despite my conviction that the evidence for persistence is strong, at some level, I still harbored a lingering feeling that maybe, just maybe, it was all mistake, a series of mirages, the product of wishful thinking.

I no longer have that feeling. Evidence still matters, but I know the birds are there and care a lot less about what others believe.

With one tuck of the wings, these hidden doubts were swept away. And that has made all the difference.

From Steven Latta:

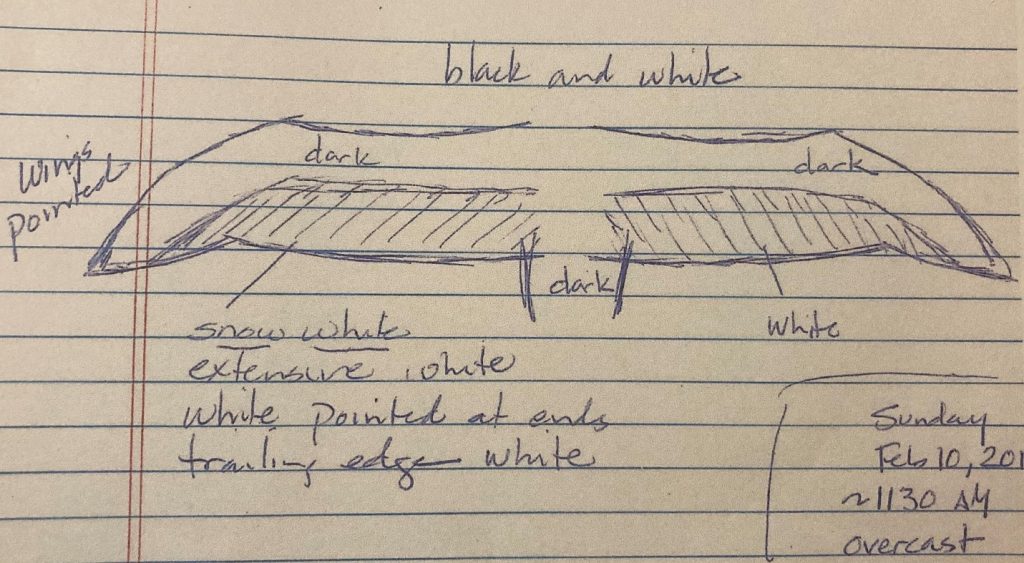

On February 10, 2019, I paired up with Mark Michaels to deploy automated recording units on a predetermined grid in prime, bottomland forest habitat. This was the heart of the project’s “hot zone” where fleeting glimpses and enticing kents had been reported. At about 1130, we had stopped momentarily when I happened to turn my head perhaps a quarter turn and caught sight of a large bird flying off about 75 yards distant. I quickly completed my turn, squared up, and froze. I did not even think to pick up my binoculars that were around my neck. Based on field notes, the bird was seen in the lower midstory, flying away from me, but angling up as though it had launched from lower down. The bird flew straight and strong with steady but unhurried flaps, but always angled up, so I always had a full view of the bird from wingtip to wingtip and across the entire dorsal area. Much to my advantage, too, the bird flew through a clear corridor or gap in the forest, so for much of its flight my view was not obscured by trees or branches. At the end of this flight, which I estimated lasted perhaps 5-6 or 8 sec, the bird appeared to “pull up” in classic woodpecker fashion as it approached the canopy of a pair of very large hardwood trees. My impression was that the bird was pulling up to land on the trunk of one of these trees, but I could not see the landing because of the intervening canopy.

The wings of the bird I saw were very long and relatively narrow, unlike a raptor or a Great Blue Heron that was seen nearby. I was very impressed by the very large size of the bird, the long pointed wings with a slight bend at the end of the wing, and the strong, direct flight. More than anything though, I was struck by the black and white pattern, and the brilliant snow white of the wings. The white formed a heavy bar across the entire trailing edge of the wing, with the white forming a point at the end of the wing where it met the black of the forewing.

I did not notice the head of the bird, perhaps because the bird was flying away from me, but I did not see any red. I did not see the shape of the tail but it was black, or at least dark, otherwise I believe I would have noted its whiteness. I did not see the ventral area as the bird was flying directly away from me and angled upwards.

From Don Scheifler:

It was a cool morning in Louisiana on October 27, 2019. I made my way through the bottomland forest, alternating between a slow walk and attentive pauses, hoping to hear the calls or double-knocks of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker. But, there was little sound of birds calling and almost no woodpeckers drumming. The quiet was occasionally broken by the distant boom of gunshots from deer hunters, as it was the season’s opening weekend.

At mid-day, while standing still and listening, I heard the rapid flaps of a bird approaching from ahead and to my right. The rate of the flaps was similar to those of a duck, but rather than the slurred flapping-whirring sound of a duck, these wingbeats were very crisp. The sound of each flap was sharp and distinct from those before. Looking up, I saw a large bird flying perhaps fifty feet above the ground, below the forest canopy but above the shorter trees. It had a hefty main body with long wings. The body of the bird was black, as well as the leading section of each wing. Most striking was the unmistakable bright white on the trailing portion of each wing, visible throughout each blurry flap. I was transfixed watching the bird fly past, focused on the wings. Because I had no habit of quickly snapping photos, I never thought about lifting the camera hanging around my neck. I just stared as the bird disappeared, flying fast, straight and level into the forest beyond my sight.

I stood there in near disbelief, struggling to decide what to do. Should I try to follow the bird? Should I sit down, immediately write a description of what I saw? Or, should I call someone? Who? I started texting my brothers about what I’d seen. A minute or two later, I heard the same wingbeats coming back, then overhead. I only got eyes on the bird again when it was just past me. Again, a big black and white bird, with bright white on the back portion of each wing. It continued past me quickly and moments later swooped down a bit, then back up, spread its wings to slow, and landed in the fork of a tree maybe 125 feet distant.

Glare from a bright but cloudy sky behind the tree made details hard to see, but I could make out the bird sitting in the tree fork. This time I raised my digital camera, aimed, pressed the photo button… and the auto-focus refused to settle on the bird! Instead, the focus constantly shifted in and out due to intervening branches from other trees. I crouched down a little, tried again, and got the same frustrating result. I then reached into my pocket, pulled out my iPhone 6s, selected the camera icon, aimed in the general direction of the bird, and tapped for a picture. I switched to video mode, aimed… and then saw that the tree fork was empty. The bird appeared to be gone. I waited a few moments, then crept to the right, maintaining distance while partially circling the tree and hoping to see the bird clinging to the bole of the tree or maybe flying away. But the bird had vanished.

Looking at my photo later, I was able to find what appeared to be the body of a bird in the fork of the tree, with the head obscured by leaves on an intervening branch. What is visible appears to include a white patch on the bird’s lower back – a major field mark for identifying Ivorybills. The photo is poor and will not be considered conclusive by most people, but it confirms to me that the bird I saw in flight that day was an Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

From Peggy L. Shrum:

The first time I heard the resonant “double-knock” of a Campephilus woodpecker was on the first day of what would be 12 years of research in the Peruvian Amazon. “Qué fue eso? What was that?” I asked my assistant, while picturing in my head a spider monkey banging a bowling-ball-sized castaña nut pod against a tree trunk. “Carpintero” he answered. “Woodpecker.” I looked up and saw a large woodpecker with a whitish bill, and felt a twinge of excitement. I knew I was seeing a relative of a bird that had recently made big headlines in my home state of Arkansas. It was 2005, and the Ivory-billed Woodpecker had possibly just been rediscovered.

Growing up in the Big Woods of Arkansas, my dad told me that I, as a child, had probably seen Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, although I doubted that I ever had, and I knew that I never would. However, I did intend to someday join an effort to learn more about them, to spend time in what once was their forest, to learn about their disappearance, and perhaps feel their absence.

I had developed a professional interest in human impacts on birds, how some birds adapt to human encroachment, even exploit it, while others simply cannot. I joined Project Coyote, now Project Principalis, in 2015 during a hiatus in my Peruvian fieldwork. Quite honestly, I don’t know if I thought then that there were any extant Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, nor was I sure if I thought it truly mattered in the larger picture. Surely if there were a few remaining, there could not be a genetically viable, recoverable population. But, I wanted to learn about the search, the field techniques, and I wanted to be in the forest.

During the first few years of spotty volunteering, I heard an occasional knock reminiscent of those Amazonian woodpeckers. I learned about the bottomland forest, about how various woodpeckers feed, roost, and nest, and I learned about trees. I learned how trees live and die, and the oh-so important gray area in between. I became familiar with the many ways various woodpeckers utilize their habitat, and what signs they leave behind.

Early in my fourth year of volunteering, I heard a very loud, clear, intentional-sounding double-knock. I felt very strongly that I had just heard an Ivorybill. However, hearing a bird and seeing a bird are vastly different things. Hearing what I felt certain was an Ivorybill did not wholly convince me that they were present. I believed that they could be, but I was still firmly standing in the “I don’t know but I want to investigate the possibility” middle ground.

Hearing an excellent double-knock and understanding the conceptual possibility of their continued presence did not at all prepare me for what I saw in February of my fifth year with the project. From my field notes of February 8, 2020, I described the following:

On the trail at 6:15 am to (an undisclosed area) with Erik Hendrickson. We were attempting to reach and replace all of the ARUs (automated recording units) in the area, but as always, this area’s terrain was rough and we were moving slowly. By around 9 am we had only reached the third ARU. We were on our way to the fourth, passing through large areas of standing water, with lots of backtracking and re-orienting ourselves. As we slowly proceeded to the fourth point, I saw a large bird on a fallen log. I stopped; Erik was beside me to my right.

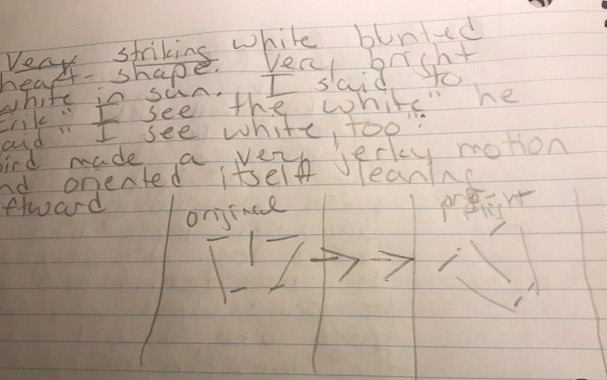

I whispered, “What is that?” The bird was roughly 20-25 m ahead of us, and oriented facing our right. The head was obscured by vegetation, and the body was visible from the chest and back. My first impression was that I was seeing a black and white chicken, with black towards the front of body, and strikingly white plumage on the rear portion. No tail was visible. As it began to sink in what I was looking at, I whispered to Erik, “I see the white.”

I then stepped to my left to use a large oak for cover as I also fumbled for my binoculars. Erik stepped to his right behind another tree. The bird then flew a few feet back, clung to the trunk of a tree, and perched vertically, 5-6 feet off the ground in bright sunlight. I very clearly saw what I can best describe as a brilliantly white, “blunted heart” shape. That is, if you drew a valentine heart and blunted the top and bottom such that the two top curves as well as the bottom point were flattened; that is what I saw on this perched bird’s folded wings.

I did not make out the head or tail. The bird cocked to its left with a jerky motion and re-oriented itself at an angle. It then flew and was gone instantly. I did not see the bird in flight, but I did see a burst of white as the bird initiated flight, and I was able to make out the shape of the bird’s left wing before it disappeared. The wing was long and pointed in shape, more like a high aspect ratio wing shape. It was not at all rounded.

We waited still and quiet for about twenty minutes but heard or saw nothing more. I immediately made field notes and sketches, and we measured off the distances and the diameter of the tree. We took a lot of photos, and placed several trail cameras, as well as an ARU at the location.

I certainly do not expect to shift anyone’s opinion on the survival of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker by sharing my experience. My own standpoint, however, is no longer in the “maybe” middle ground. I am certain that I saw an Ivory-billed Woodpecker. I am certain on a professional, intellectual, and an emotional level. I am an experienced-enough field biologist to know and understand that it is always appropriate to leave room for question and doubt when drawing conclusions. However, even if I allow myself to explore other possibilities, I cannot make the bird that I saw into anything other than an Ivorybill.

From Erik Hendrickson:

My sighting of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker occurred in mature bottomland hardwood forest on February 15, 2020, at about 9:45 am. This was a horrible sighting (because my description is lacking detail that I know others will want), but it was also one of the most incredible sightings in all my birding experiences, and the place, circumstances, what I saw, and behavior leaves no doubt in my mind as to identification. The following account is based on notes that I made in the field, except where otherwise indicated.

My search partner, Peggy Shrum, and I had walked in that day about 1.1 miles, although we probably covered at least 1.5 miles or more skirting channels and other obstacles. Our purpose was to install a trail camera at a spot where Peggy had observed an Ivory-billed Woodpecker one week prior, on February 8, 2020.

The week interval between Peggy’s sighting and my sighting was spent engaged in typical activities for this search season. We rose early, and when weather and water levels permitted, we were in the field by early morning. Peggy was an experienced field biologist, and I had been a serious birder for decades – we knew how to observe, and became more familiar with the search area each time we went in. I felt like one of the seasonal biological technicians (“bio techs”) I envied during my career as an engineer with the National Park Service; while I was stuck at my computer, they went out into the field to do work.

Much of our time in the woods was walking quietly, but purposefully, to various locations to install Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs) and trail cameras, or to swap out batteries or SD cards. It wasn’t hard science – it was being “in the woods,” every day, and observing the habitat and the animals (especially birds), and always being on alert for “something different.” Our pace was fast enough that we were physically tired at the end of the day, but not so fast that we didn’t have time to observe how the natural world changed a little each day. We routinely saw birds, and raised our binoculars to identify them – a skill practiced repeatedly, even if we could tell with naked eye that the bird was other than an Ivory-billed Woodpecker. We were observers, and focused on what we could see and hear and smell. That was our purpose, and every day we got better at observing in that particular habitat.

On Saturday, February 15, we were navigating to the place where Peggy had observed an Ivorybill the week before. One last channel blocked our route. On a day with lower water levels, we likely would have found a path forward at a shallow spot, or over an exposed log, but on this day we went up and down the channel, not finding a good place to cross. Finally, Peggy decided to crawl across a long, narrow log and into a tangle of vines on the opposite side. The vines were so thick I was forced to follow on hands and knees also.

Many of the details in my account are not important in terms of what I observed, but they are the details that one remembers when something extraordinary happens: I reached the end of the log, and stepped awkwardly and slowly through the vines, moving towards the clearing that was our destination. When finally clear of the vines, I bent forward to wipe the palms of my hands on my thighs, then straightened up and took hold of my smart phone that dangled from my neck.

I looked down at the GPS app running on my phone and verified I was “on line” with our destination, and raised my head to look forward. This is how I mostly used GPS in the bottomland: I would square my shoulders to the bearing indicated by the GPS, then look forward for a landmark that I could walk towards so that I could keep observing while walking. Once I arrived at the landmark (often a large tree); I would pause, look down at the GPS, and repeat the process.

This time, looking ahead for a landmark, I looked across a clearing, and saw a blur of wings. The blur was at ground level, or just above the ground. The blur was mostly white – part of it was brilliant white, and other parts (smaller parts) faded to grayish-white. The blur seemed to be overall spherical. It was obviously a bird, and the blur went powerfully upwards (I estimated at an 80 degree angle) into the leafless crown of a tree.

I saw no field marks that we associate with Ivory-billed Woodpecker: I did not see the head, or bill, or neck or body, or the tail – it was just a powerful, spherical blur of white wings, launching powerfully in a near vertical ascent. It was startling to see. (I suspect I startled the bird.) It was an amazing display of power. It was larger and more powerful than any passerine, or any other bird I saw in the bottomland. It flew upward unlike any bird I have ever seen anywhere. It happened in a startling second.

None of these observations are considered “field marks.” But they identified the bird. I whisper-called for Peggy, and we stood behind a 4-foot diameter oak. In the tree canopy ahead, I saw a large, “dark and light” bird fly from right to left – but did not see where it flew from, or where it flew to; and I didn’t see any details of the bird. I saw the bird “move” through the canopy again – a shorter flight, and it was again completely obscured before and after the movement.

Peggy and I finally decided to move forward, she to the left and me to the right of the big oak. Within a minute or two, Peggy saw “movement” – enough to tell the bird had launched, and called out, “It’s gone.”

I have participated in searches in this bottomland hardwood forest for a cumulative 12 weeks, specifically looking for birds, and seeing all of the expected species, from small passerines to the larger Northern Flicker, American Crow, Pileated Woodpecker, Barred Owl, Great Blue Heron, Red-shouldered Hawk, and Turkey Vulture (as well as the rarer Bald Eagle, Golden Eagle, and Black Vulture). Although it’s always difficult to judge size and distance in the field, several hours after my observation I noted that the bird I saw with an unobstructed view was the size of (or slightly smaller than) a Red-shouldered Hawk, a very common species in our study area. I later determined that this puts my observation in the size range of American Crow, a species often used for size comparisons with Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

The visual impact of large wings, beating rapidly to launch a large bird and sustain its escape flight created the motion my eye and mind interpreted as blur. We were in exactly the right habitat for the species. When I first saw the bird, it appeared to be on the ground; flew powerfully upward for a height I’ve estimated as 80 feet, and made short flights through the tree canopy – behavior inconsistent with herons, ducks, raptors, and kingfishers. In the two short canopy flights I observed, the bird was large enough to be detected, but it never perched, or paused, or lingered to engage in any activity. The quality of the bird’s white coloration (mostly white, and its brightness) was significant; it was the dominant color that I saw, and comparable only to white egrets I’ve observed rarely in the bottomland. The bird wasn’t bold, nor vocal; it wasn’t mostly dark, or mostly blue like the common corvids in the area.

Much has been written and discussed about how we humans can confuse Ivory-billed Woodpecker with other species, especially the Pileated Woodpecker. I understand that my sighting is awful, in so far as I saw none of what we consider classic field marks of an Ivorybill and I had no opportunity to observe the bird for any length of time. I saw an Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Arkansas in 2005, including field marks and behavior, and that experience was useful for my 2020 observation. Steeped in as much knowledge as I can absorb of the bird’s natural history, and of previous searches, historical and recent, I readily accept that this observation is just one more unconvincing report. But, I am also confident in identifying this bird as an Ivory-billed Woodpecker; to me, it is second only in excitement to my first observation in Arkansas.

From Jay Tischendorf, DVM:

On Sunday, May 16, 2021, while engaged in fieldwork with the National Aviary and Project Principalis, I was alone and driving at approximately 32-40 km/hr (20-25 mph) along a road within the bottomland hardwood swamp forest of Louisiana. At the time and location of this observation, the road was straight and there were no other vehicles in sight. At 1140, a black and white bird flew directly across the road in front of me. It had emerged from the mostly upland forest immediately adjacent to the roadway. The bird was roughly the size of a crow and was traveling east to west. It was flying steadily and level at approximately 6-9 m (20-30 ft) altitude. When I first saw it, the bird was approximately 6-9 m (20-30 ft) in front of the vehicle.

Almost instantaneously, upon seeing a black and white bird of this size, I knew it was either a Pileated or an Ivory-billed woodpecker. My instantaneous and instinctive assumption was that this would be a Pileated Woodpecker, which are quite common in the area. Almost simultaneously, though, I realized that this bird seemed to have too much white and be too large to be a Pileated. I realized then I needed to focus and be very careful with this observation, taking in as much as I possibly could as fast and accurately as possible, for I realized this was quite possibly an Ivory-billed Woodpecker and that this would likely be a fleeting experience. At the same time all of this was racing through my head, I was watching the bird, slowing the vehicle, and bringing it to a stop. The bird continued flying steadily into and onward through the upland forest on the far side of the road.

Overall, I observed this bird for 5-8 sec as it flew approximately 45-68 m (50-75 yards) before disappearing into the forest. At one point, approximately 3-4 sec into the observation, I literally stated aloud to myself, “Leading and trailing edge.” This was in reference to the pattern of white I was able to glimpse on the underside of the bird’s wings as it passed overhead in front of me and then, as it continued moving, from an oblique perspective. The wings were not rounded and seemed too long to be a Pileated, and in fact even longer than those of a crow.

As noted above, the flight was steady, straight, and level. At no point was there any undulation in the aspect of flight, or interruption in the bird’s steady and deliberate wingbeats. I can best describe the quality of the flight as “powerful and purposeful.” It was moving rapidly or perhaps even hastily, but, if I anthropomorphize, it did not seem to be in a panic. The bird never stopped flapping or erred from its straight and steady flight, even as it passed from the clear airspace of the roadway into and onward through the forest. Other than a slight twist or tilt to avoid a tree trunk, there was no pause to the wingbeats, no undulation to the flight path, and no fluttering or faltering quality to the flight. Additionally, the bird had a stiff wing movement, which I would describe more as a steady “pump” rather than a floppy, sloppy flap.

Upon losing sight of the bird, I jotted down notes about the observation and marked the location with my cellphone. For future reference, I also marked a nearby tree. I also launched a camera drone in hopes of possibly capturing the bird on film, but did not encounter the bird again.

Habitat is the one and only factor associated with this observation that would suggest Pileated to me. This area is essentially all upland habitat, at least from what is visible from the road. However, the map of that area shows waterways or tributaries located in bottomland hardwood swamps within 1.6 km (1 mile) on either side of the road. Additionally, the drone footage I captured immediately after the observation actually shows a narrow strip of deciduous trees running through the upland forest at a 90˚ angle to the road and extending from the uplands at the road to bottomlands and hardwood swamp forest nearby.

Conveniently, within a few minutes of continuing my drive after the drone flight over the area, I saw 2-3 crows flying under similar conditions (altitude, habitat, sky conditions) to that of the mystery bird I had just seen. They provided solid reinforcement for comparing not just size but shape.

Finally, I would like to comment on the element of surprise when this sighting occurred. In this regard, one needs to understand that in ~5 yr of involvement with Project Principalis, I have never entered these woods thinking I will even see an Ivory-billed Woodpecker; I have always operated with the matter-of-fact belief I would actually never see an Ivorybill. In short, getting a glimpse of the Ghost Bird has never been my goal in working with Project Principalis, but rather just to know that I am helping in the search to keep its legacy alive. As would be true in any instance when some sort of wildlife suddenly manifests itself in front of you, I was entirely taken by surprise when I first saw this bird. The instantaneous and multi-layered thoughts, reactions, and reflexes that occur when startled in this fashion are complex, particularly when it potentially involves a species considered extinct for the past 8 decades.

I have concluded that this bird could only have been a Pileated or Ivory-billed Woodpecker. It is only with extreme, and in the end truly unconvincing effort, that I can even come close to making it out to be the former: I am convinced I saw an Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Press inquiries: please contact [email protected] or call 412-258-1144.

Support this important project by directing your donation to Project Principalis using the dropdown menu at this link:

Support Our Work